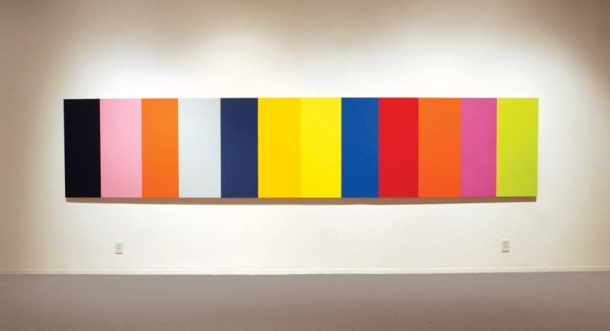

Brent: You have been working on areas of color; vertical or horizontal bands of either matte paint or gloss paint with sometimes both present in the one painting at the same time. The structure between two areas of color, you couldn’t really call it a line, though, well, in the material – a space where something stops and then something starts.

You have used aluminum supports for some time now. They sit well, both functioning as unadorned surface where paint can just glide over, and as a sheer and clean plane on which to see the color, the paint.

What brought you to use these supports? Do you do all the preparation yourself? If so could you tell what that entails to get something to sit on the wall, for paint to sit upon the support?

Kasarian: I’ve been using aluminum since about 1996 or so. I discovered it as a painting support in graduate school at The Art Institute of Chicago. I was making these fairly reductive paintings on canvas and was really struggling with what to do with the sides of the canvas: do I paint the edges of the canvas? Do I tape the sides so they stay clean? Are the sides of the canvas with the paint build up an important index of the process or a distraction from what’s happening on the surface plane? How thick or thin should I make the stretcher? I tried a lot of different ideas with this, thick stretchers, thin  stretchers, etc. and it was not satisfying. The sides of the canvas were always another plane to deal with in relationship to the surface plane, and I was just not interested in making paintings on the sides of my paintings.

stretchers, etc. and it was not satisfying. The sides of the canvas were always another plane to deal with in relationship to the surface plane, and I was just not interested in making paintings on the sides of my paintings.

Another aspect of painting on canvas was that I would spend large amounts of time building up the surface of the painting, priming the canvas with oil primer and painting knife in several layers, sanding them, repeating, until the canvas texture was basically gone and only a smooth surface remained. While in some ways I enjoyed the process of building the surface, it also seemed logical to ask: why paint on this canvas surface if I don’t really even start adding color until the canvas surface is hidden? Or, why not just start on a smooth surface?

I tried some wood surfaces, which was OK but not satisfying. I worked in the metal & woodshop of the school at the time, and one of the guys from the metal shop just said one day, “Hey, I’ve got some aluminum, why don’t you try that?” The first paintings were constructed from 1/16” aluminum that was laminated onto 1/4” Masonite. I then added a beveled frame on the back of the Masonite, and this was when the idea came to “float” the panels off the wall by inserting the frame structure several inches inside of the edge of the panels. This immediately solved my side of the painting problem (I could deal with a 5/16” panel edge) and also gave the paintings an immediate presence on the wall, with the surface plane suspended about 1 _” off the wall. It immediately just felt right. I used this laminated aluminum method for about the next 3 years.

Later, due to some technical problems1, and because I received an artist grant, I was able to have a group of 10 panels constructed completely of aluminum. This was the next stage, so to speak, because once I saw the panels of 1/8” aluminum mounted one-inch from the wall with an aluminum bracket, the earlier laminated works seemed more like rough models for these more “machined” panels. The presence was better, more extreme, with this thin plane just suspended in space, with even less edge to deal with. Also, around this time, I saw a grey monochrome painting of Blinky Palermo that was done on thin steel at Art Chicago on Navy Pier, and it was like, whoah, that is sooo sweet.

that is sooo sweet.

As far as how the aluminum panels are made, the process is fairly straightforward. Two one-inch right-angled brackets of aluminum are welded to the back of the 1/8” aluminum panel, inserted a few inches from each edge of the panel, one near the top, one near the bottom. Two holes are drilled in each bracket on the painting, near the ends. A third section of the right-angled aluminum serves as a bracket, which is mounted on the wall. Two nubs of aluminum are welded to this bracket and fit into the holes on the top bracket of the panel, locking the panel to the wall. It sounds complicated to write all this, but the system is very straightforward.

One aspect of this system I really like is that the top edge of the painting can be changed, since I can flip the panels upside down to hang on the other bracket. The panels can also be interchanged with other panels of the same size, so when I’m installing an exhibition, I can mount the holding brackets on the wall and then switch around both the order and orientation of the paintings.

As far as surface preparation, welding the bracket on the back of the panel leaves a series of small bumps on the surface of panel. They look sort of like raised lines, and though slight, they need to be sanded off. So I (or my studio assistant) use a palm sander to sand the surface of the panels, focusing on the raised welds. The surface is then degreased, usually with turpenoid simply because it is less fume-y then other solvents, and then primed with Zinser multi-purpose primer, which you can buy at Lowe’s or Home Depot, etc. It’s a great primer, it sticks to anything (even if the surface is not roughed up or degreased), and it holds oil or acrylic paint very nicely. The primed surface is sanded several more times, usually about 3 or so, and primed in between. The sanding takes down the weld mark, and each layer of priming, applied with a foam roller, builds up the surface, until eventually the bumps are gone and a smooth surface remains. It probably sounds like a pain, but it actually is quite easy. The primer dries fast, in a couple of hours, so in about 2 days or so, I can get a new group of panels prepared and ready to paint.

1. The laminated method was economical and worked fine, until one day in mid-January in Chicago, the heating system went down in my studio building. My studio mate, painter Matthew Girson, called and said I better get over there right away. The boiler had shutdown in the middle of the night, and the temperature in the entire building dropped to about zero degrees. The boiler was then turned back on full blast, and in a few hours the temperature went back up to about 70 degrees, tropical-style. The composite panels could not take the stress of this sudden temperature change, and the laminated aluminum bubbled up and popped off the surface of the Masonite and wood supports. It was extremely disconcerting, and the set of works was completely ruined.

Brent: And then they are ready to work on.

After you started working with the aluminum panels for a while were there compositional changes taking place as well? Or was it just a new support, and painting carried on as usual, change taking place for perhaps completely different reasons?

Kasarian: Yes, there were compositional changes, but it started more with the paint application. When I began working on the aluminum, I had been using this mixture of really thick, slow oil paint, with wax medium and calcium carbonate added to really slow the paint down, so that it applied like a half-dried out can of drywall joint compound. Initially, I really liked how the slow, paste-y paint sat on top of the slick, smooth “fast” aluminum. But it took me like 6 months to make 3 paintings and got kind of old. I still love the surface of those paintings, they’re very radiant and layered, but the process was bogging me down. These were mostly monochrome paintings, with primarily muted, earthy colors.

When I started to thin down the paint initially, I was still using oil, but it made the process speed up, and I also began to make color divisions in the panels, something that at the time was a really big jump. The color slowly started to become more vibrant and less earthy. And then I did something I had never thought I would do. Up until this point, all of the paint surfaces were highly matte in sheen, absorbing light. At the time, I detested glossy surfaces. I’m not sure exactly why, but I think I associated glossy surfaces with fakeness, like plastic or something. Glossy was superficial, slick, commercial, sellable…not what I was interested in. But then after making these matte surfaces for several years, I just needed to change it up; all these “slow” surfaces were just  bogging me down.

bogging me down.

One of the most memorable critique phrases I’ve ever heard about my work was from around this time when an artist told me: “Your paintings look like Yves Klein went for a walk in the mud!”

So I started to use some gloss oil medium, like Galkyd, with the paint, and it just was this breakthrough that I really needed. It probably seems funny to some that using a glossy paint was such a big deal or a big change for me, and it sounds funny to write about it, but it really was a big move at the time! Later, this lead to using One Shot enamel paints. This type of paint just sits so awesome on the aluminum, and I began combining the glossy One Shot enamels with the matte, velvety surfaces of acrylic Flashe.

So back to the initial question about composition, going from the thick oil to adding glossy paint, and then to the One Shot and Flashe, the paintings changed significantly. Color became more vibrant, especially with the colors available right out of the can with the One Shot enamels, and I also let go of the idea that the paintings had to have only 2 or 3 colors, and just let myself do some more multicolor stripe paintings. My detest for the superficial glossiness became more of a love of this surface, and I really became interested in how a fast, high-gloss surface could be placed next to a slow, super-matte surface, and not only create an intense visual contrast and edge, but also situate a sort of commercial, candy-colored “pop” surface (like a Warhol pink) next to a super-matte, “deep” Modernist-type surface (like a Reinhardt black). Does that make sense?

Brent: What year are we talking?

Kasarian: 1997–1998 Started working with aluminum. 1999 Moved primarily to aluminum, with all aluminum panels. 2000–2002 Color shift. Started to use One Shot enamels. 2003–2004 Started combining One Shot enamels and Flashe paint. 2004–2007 Worked primarily with One Shot and flashe on aluminum, with some works on paper. 2008–2009 Began working with Golden matte acrylic to replace flashe.

primarily to aluminum, with all aluminum panels. 2000–2002 Color shift. Started to use One Shot enamels. 2003–2004 Started combining One Shot enamels and Flashe paint. 2004–2007 Worked primarily with One Shot and flashe on aluminum, with some works on paper. 2008–2009 Began working with Golden matte acrylic to replace flashe.

Brent: So more colors started to appear. They came up as stripes. You wanted more color and different color all on the one surface. Was composition mostly important at the time? Or was it more getting the ‘clang’, or the ‘sing’, that was important, and you’d just shuffle the color along, in their container, until it all came up?

Kasarian: It was mostly that I would start laying colors down, and look for when the color would really hold together. I don’t really think of it in terms of composition, but more as a surface to be divided by a few or many colors. At first, there was some hesitation to divide a surface into many bands of colors or stripes. I had been so accustomed to a certain minimal look, that having that many bands of color seemed a little strange, sort of like, can I allow that into this process? But it made sense at the time, and I liked how it was new to the process, so I just let it happen. This was around 2003–2004. Also, I feel like it sort of set the parameters for my work: on an aluminum panels, there can be a few or many bands of color, and I’m comfortable to work within this setting. I can be very minimal with the color bands, or I can really divide the surface with many bands of color.

Brent: It’s interesting in a way: You have a range of colors, you can mix them, but you know you are going to do bars.

Do you sometimes think approaching painting in this way limiting – working with such strong precepts? Or, another way, do you think in terms of there are so many choices…and it is a wonder you are able to make a start?

Kasarian: I do think approaching painting in this way is limiting, and that’s part of what is so engaging for me about it. What are the possibilities within these limitations? How many possible combinations of color/amount/proportion/surface are there with this set of colors? When I start to work, it quickly becomes apparent that there are so many possibilities that this way of working is not really limited, but presents a vast number of problems and solutions to deal with. It’s usually not a question about where to start. It’s very straight forward: here is a set of colors that I’m interested in at the time, divide the panel into horizontal or vertical bars, and then start applying color. That’s the really exciting part, starting the problem, the process of applying the color, wow, it’s great. The difficult part comes more on the “end” of the process…where do I stop? Because in the process, it’s like, what if I put this color here? What if I placed a gray here? What if there is an orange bar here? What if the orange bar was a half-inch wider? What if the gray area were an inch thinner? What if the gray was warmer? Or more yellow? Or glossy? This is terribly exciting for me, and I love to just keep making those decisions and changes over and over again…like maybe, just maybe something more will happen on the panel than is happening now. When to stop this process can be a real problem, and I paint and re-paint paintings multiple times.

within these limitations? How many possible combinations of color/amount/proportion/surface are there with this set of colors? When I start to work, it quickly becomes apparent that there are so many possibilities that this way of working is not really limited, but presents a vast number of problems and solutions to deal with. It’s usually not a question about where to start. It’s very straight forward: here is a set of colors that I’m interested in at the time, divide the panel into horizontal or vertical bars, and then start applying color. That’s the really exciting part, starting the problem, the process of applying the color, wow, it’s great. The difficult part comes more on the “end” of the process…where do I stop? Because in the process, it’s like, what if I put this color here? What if I placed a gray here? What if there is an orange bar here? What if the orange bar was a half-inch wider? What if the gray area were an inch thinner? What if the gray was warmer? Or more yellow? Or glossy? This is terribly exciting for me, and I love to just keep making those decisions and changes over and over again…like maybe, just maybe something more will happen on the panel than is happening now. When to stop this process can be a real problem, and I paint and re-paint paintings multiple times.

Brent: I think you said somewhere that no work is really absolutely complete. But there is a state isn’t there… I don’t know… a state where you actually ‘feel’ that a work is succeeding? Can you pinpoint that, those moments… perhaps days pass before you decide… ‘OK’… ‘I’m happy with that!

Kasarian: Yes, there is a state that I’m aiming for. While the painting process is exciting, it’s not aimless wandering so to speak. But to pinpoint that state is very difficult. I spend a lot of time looking near the end of the process, a lot of time just sitting and looking at the work. This can be difficult because my time in the studio is more limited these days, between teaching and family life. Sometimes when I get in the studio I just want to paint so badly, it can be challenging to get to the end of a group of paintings and just sit and look at them. In the past, I’ve used a sports metaphor to try and describe the state I’m aiming for: the Zone. Like when an athlete is really concentrating so intensely that they are performing at such a high level mentally, and everything is just clicking for them. I play goalie in ice hockey, so this is the state where the game just seems to move  more slowly than usual, and you’re just on, stopping every shot. And mentally, it’s just like everything is so clear, so clear and so intense. I like this metaphor because I get to talk about hockey and it works nicely in an artist lecture! But this isn’t exactly it either, it’s not exactly the same, but it does involve vision, like your eyes are really working with your mind and body, really connected.

more slowly than usual, and you’re just on, stopping every shot. And mentally, it’s just like everything is so clear, so clear and so intense. I like this metaphor because I get to talk about hockey and it works nicely in an artist lecture! But this isn’t exactly it either, it’s not exactly the same, but it does involve vision, like your eyes are really working with your mind and body, really connected.

It’s like when you put a group of colors together, and it’s just right, it all comes together. There’s an aspect of unity or totality, where though you may have a panel made up of several different colors, it holds together as a whole, it reads as one unified work. And the whole becomes something more than just this color sitting next to that color, something happens that just clicks, and the colors open up and become more than the two or more than the group when put together. Really, I think this is what makes the work more than color exercises, so to speak. I mean they are color exercises, but when the paintings really work, there’s something more there than a formal arrangement of color, or so I believe.

I went to hear David Batchelor talk at MoMA last spring during the Color Chart exhibition, and he was talking about how his new work was trying to get color that was “uncontained”, by using light to bring color outside of the boundaries of a rectangular, “contained” color work, reflecting colored light into the room and so forth. While this made sense to me, my thought at the time was that if you use color in a certain way, it does become “uncontained”, it expands, it becomes bigger that the surface it sits on, even though it is physically “contained” on a limited surface, like a 24” x 48” panel, it seems at times to open up and expand beyond it’s physical dimensions. The work takes on a presence that is bigger than it’s physical size, vaster, more expansive. Maybe that’s the state I aim for, it’s tricky, it’s elusive, and it can be difficult to recognize.

Sometimes when I’ve been out the studio for a while, and I come back in, I have to be careful not to just paint over all my paintings again! I can forget what I’m doing, and so I need to spend some time with the work to get back in the grove, to remember what I’m aiming for.

Brent: There’s a greater expanse of color in very recent work.

A few years ago I noticed something very new. You seemed to work in and out of it for a while…

In L.A. recently I could see a really good example of what I would consider an earlier piece where this color and space is structurally beautiful, very active and clear. The newer pieces hold that space though in a new state as ‘sound’ – coming out as painting. I say sound, because if I talk just about color, or color container, I’m going to get stuck on the local physicality of paint on a surface. What I experienced was ‘vibration’ and ‘arrangement’, not just expanded areas of color or more minimal areas. This new arrangement comes out very much into the air—you can feel the air filling, moving toward you in a very elegant and ‘sounding’ way.

In L.A. recently I could see a really good example of what I would consider an earlier piece where this color and space is structurally beautiful, very active and clear. The newer pieces hold that space though in a new state as ‘sound’ – coming out as painting. I say sound, because if I talk just about color, or color container, I’m going to get stuck on the local physicality of paint on a surface. What I experienced was ‘vibration’ and ‘arrangement’, not just expanded areas of color or more minimal areas. This new arrangement comes out very much into the air—you can feel the air filling, moving toward you in a very elegant and ‘sounding’ way.

Kasarian: Yes, that’s a nice description. Currently, I’m working on a set of thirty aluminum panels, 24” x 48” each, and just running with the color variation. This is the first time in a while that I’ve had this many panels going on all at once, so I’m really excited to be moving through a variety of color ideas more quickly, to really see what I can do with the group of paintings. The color is generally more “stretched out”, with a central color surrounded by one or two adjacent colors. I also always have smaller panels around the studio that I continue to paint, usually with thinner bands of color. In addition to the small panels, I keep a notebook of paintings and do some work on paper, to keep getting color ideas out there and to keep things moving. At times I’ve become so focused on one set of paintings, like a set of ten, that I just keep re-painting them over and over again. While this can be good in some ways, I’m trying to get more ideas out more fluidly by keeping smaller panels around and by working on paper. Summer is coming, and I’m on sabbatical next fall, and I just can’t wait…painting, and playing some hockey in between, and painting some more…

Nice interview. I have to come back to it . Kasarian – thanks for sharing all that technical info. Its very interesting as is your process.

Just great, Brent,

and Kasarian — thanks so much

Kate

I wish I could see these in person – on the screen the colors glow and do seem to expand. The economy of means feels generous here. Thank you!

Thanks for sharing so much of your process. Your brain always gets my brain going.

Very cool interview. It gives great insight into Dane’s paintings.

Thanks for this, I feel like I know a little more about surface and aluminum…really great!