Brent: Here we are in the realm of architecture, painting, sculpture, photography, and digital imaging. You are an artist, curator, and an agent provocateur, among other things. Where do we start?

Guido: Agent provocateur?

Brent: Maybe a better label would be DIY. If an opportunity is not there you organize, find a place, and do it.

You happily, or disruptively, ask questions about genre–merge them–a large photograph of your studio in a recent state of demolition/reconstruction may secure the point I’m trying to make here. This image also turns up in a small IS Box, which is your project, as well functions as promotion, as well as a business–addresses something of the AP, or not?

I’ll let you answer.

Guido: To be honest my original background is in photography (and early video, 1986-1988), but ended up doing  sculpture at the Academia for Visual Arts (1989-1994). Sculpture, I thought at that time, would give me the ultimate freedom within the field of visual arts, as it would be possible to incorporate anything in sculpture/installation type work. But funnily enough, slowly between 1998 and 2004 (for reasons I will skip here), I have been incorporating sculpture into painting. Since 2003, when the digital photography became more of a factor, I bought my first digital camera–initially for photographing my own work and for capturing sketches but some of these photos were good as is. In the end technique is only a way of getting somewhere. Maybe I get bored easily, but I would rather think that I get triggered by new possibilities.

sculpture at the Academia for Visual Arts (1989-1994). Sculpture, I thought at that time, would give me the ultimate freedom within the field of visual arts, as it would be possible to incorporate anything in sculpture/installation type work. But funnily enough, slowly between 1998 and 2004 (for reasons I will skip here), I have been incorporating sculpture into painting. Since 2003, when the digital photography became more of a factor, I bought my first digital camera–initially for photographing my own work and for capturing sketches but some of these photos were good as is. In the end technique is only a way of getting somewhere. Maybe I get bored easily, but I would rather think that I get triggered by new possibilities.

The meaning of the work lay also in the way people respond to it.

Today, I came to the conclusion that art may make us human… but a collector, for instance, who lives with art in his/her home, brings art to life. Human beings are social animals and art is a social connector.

The commercial part is that if you hardly sell it is impossible to keep going. Having said that, I have a very hard time selling my soul to a gallery. Especially if a gallery asks for the exclusive rights to show my work but won’t give me a monthly stipend, which is sometimes the case here in The Netherlands.

I guess for me, my art can expand in the best sense when my position as an artist is as fluid as possible and I think the way I work as an artist and as co-director of IS-projects is close to this ideal. Though, as mentioned, flexibility is paramount.

…You know, you say DIY, but I always get invitations to show.

Brent: Understood.

In your own practice as an artist early works take on architectural form, hints to illusion, as well as metaphor–can be made up of  parts to form recognizable things, things swing, sit, can also be specific as well as be seen somehow responding to the gossamer of the photograph.

parts to form recognizable things, things swing, sit, can also be specific as well as be seen somehow responding to the gossamer of the photograph.

Guido: True. I think it all relates to one specific experience I had somewhere in 1998 while walking in Leiden.

Brent: And that was?

Guido: I was walking on a very bright midwinter day along one of Leiden’s canals which is connected by narrow streets to the big shopping street. The sun sat just above the horizon and was shining straight into my face. As I passed a side street I looked down–both sides were completely in shadow and together they formed a black frame. The depth of the street had disappeared with the sun-bathed shop fronts at the end of the street looking as if they were projected onto a film screen.

I thought this incredible.

Not something that I needed to go home and paint, but more in the way that it left something dangling, about the notion of reality, of what it is, or might be.

Related, too, is the notion of the Renaissance central perspective, which requires the viewer to stand in front of a painting to see a due representation of a three-dimensional place, the thought of what happens to the perspective of a painting when viewed at an angle; or when passing by it, the shifting of position: the viewer may not be stationary in this, the third dimension, while still engaging the painting. And while aware of the perspective in the painting, the reality of it is, at the same time a viewer can see the painting as a thing, the different aspects of it as you move around… closer, further away.

Brent: Another spatial sense… you make doors that swing.

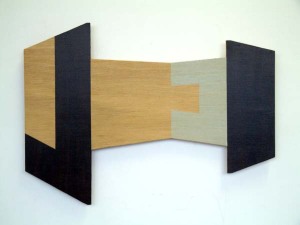

Guido: You are referring to, of course, the work ‘Passages’, made back in 2002. I was interested in playing with the problem of fixed point, keeping in mind the renaissance fixed point perspective that we talked about earlier, and I was thinking about how to make something that you could pass by, engage the multiple shifting points of the piece, at the same time know what is wholly there. I made a version so big (Passages II) that it was impossible to take in within one view except from an angle, thus came about the ‘door work’ that you are referring to: doors as canvasses.

I liked the shifting combination and perspective and also the fact that the viewer needed to actively participate to experience the work.

‘Passages I’ consisted of 5 doors fixed to each other by a single pole to the next. They were hinged like normal doors (They were normal DIY doors actually including their posts) and the viewer was invited to walk through and participate. But actually hardly anyone did this, instead seemed happy to move around and view the work from what you could call ‘the outside’.

Funny you ask because, just now, I am working on a new door work that will be exhibited in Leiden (Scheltema project of Stedlijk Museum de Lakenhal) in March this year.

Brent: After these early door pieces it would appear that you went back to this fixed point perspective, in small works, acrylic on wood, and mounted photographs of views seen through a particular frame of vision, whether they be doors, windows, or in one photograph a large duct. In the small works on wood you have this architectural space of a structure or room that appears to sit on one single plane that suggests an illusionist space from the inside while at the same time exposing part of the outside. Where the viewer or participator is in all this, what position they take to understand this kind of work, does that play a role, or does it matter? The photographs are small also, but suggest something larger this time the ‘suggestion’ an architectural element that grants access to but also diminishes the view to another outside or through the view place or space.

Guido: It would appear… yes. But with the wooden works I don’t really see the difference, they are still more object than painting. And it seems fascinating how small works can also be intimate and monumental at the same time. But not only this let’s add also the central and the shifted, the concrete and the abstract, along with the traditional notions of the object and subject in painting.

That said, I can’t tell the viewer what to see. Yet it has also crossed my mind that what I might consider to be personal and intimate may also come across as possibly well received by a large audience in that it reads multifarious, each individual getting something different.

I bought my first digital camera for completely different reasons back in 2003 but that was a new start to make photos. What I liked at that time was the possibility of sharing my point of view in a more direct manner with the public.

Even though a camera is a central perspective tool, most of my photos still open the viewer to an unexpected experience within perspective. In the images you mention the camera is often looking up, can be 10cm from the floor, or be a reflected image. The tunnel photos, of course, have that extreme renaissance central point of view as a counter position.

The duct is a ‘ski tunnel’. I took the picture in the summer. In fact, it is a large duct, approximately 400cm in diameter.

What struck me the most is that I tend to take photos through something, a door, a gap, or a window. This frame, very much like the frame of the viewfinder, blocks information, like the earlier impression relayed, the walls in the street on that winter’s day.

Brent: And so the paintings that followed were small, focusing on positive/negative, absent/present spaces, silhouettes of doors, walls and floors, a graphic rendering of interior architectural housings.

Guido: What does one see? How does one look? I am interested in these questions of perception. We live in the same world but no one sees it the same way.

Brent: ‘Transitions’, from an exhibition at ‘Le petit port’, 2006, pieces that primarily get worked with/in the actual internal architecture, do you think what you are doing here is still called painting? And, just to inquire, what are your thoughts on the framing device that bordered or supported painting for so long, once it became plain, or disappeared altogether, didn’t architecture tend to dominate the way we saw painting… as you say, painting became an object, though within another object, one that very much informed our perception, though because of scale we aren’t able see the whole thing, only aspects–a window, there a door, some furniture. And painting, as an ‘object’, became increasingly close to being read as decoration, sometimes still appealing to the illusionary, other times, flipping, into Objecthood.

How did ‘Transitions’ come about?

Guido: The Transitions exhibition was more a work in progress than a gallery show, really. Le Petit Port is just around the  corner. Therefore it seemed logical to experiment and work in the gallery rather than just hanging and showing there for six weeks. So, I worked right there with paper, a beamer, cameras (still and video), a printer and a computer. When I wasn’t there to work, paintings or photographs from the stock or studio were introduced. I used the title ‘Transitions’ because of the shift in focus from painting and installation back to photography and new experimentation with digital printing and then even further, adding digital printing to painting. The title also referred to the continuing process of the exhibition but, and, also to the more general sense of making art as an ongoing thing. Some things I ‘showed’ for five minutes, others for two weeks. It has been a very creative period.

corner. Therefore it seemed logical to experiment and work in the gallery rather than just hanging and showing there for six weeks. So, I worked right there with paper, a beamer, cameras (still and video), a printer and a computer. When I wasn’t there to work, paintings or photographs from the stock or studio were introduced. I used the title ‘Transitions’ because of the shift in focus from painting and installation back to photography and new experimentation with digital printing and then even further, adding digital printing to painting. The title also referred to the continuing process of the exhibition but, and, also to the more general sense of making art as an ongoing thing. Some things I ‘showed’ for five minutes, others for two weeks. It has been a very creative period.

Thinking about the frame, especially when I think of the heavy (neo) classical frame, they are probably derived from religious thinking, designed and used as an altar to separate the fictional world from the real. But really I’m not so interested in that. My interest is more the stepping away from the convention of a painting with its rectangular space, a window to another world and compositional verisimilitude, to something more object yet planar, yet with the suggestion of a plane complex–a folding/unfolding of the thing in time/space.

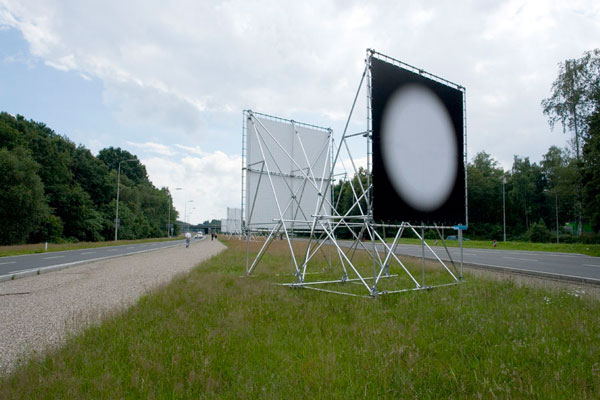

Brent: You did some billboards around the same time, a pair of blurry digital dots blown up to 400 cm x 400 cm, scaffolding, each facing the oncoming traffic, speed dots? I like them. I’m in a car, driving towards them, the dots are getting bigger, darker, blurrier… how do they fit in to what we have been taking about so far?

Guido: The billboard was a commission for a temporary Center for Visual Arts in Apeldoorn. It was a series of works done by various artists. Later, they put it along Apeldoorn’s entrance road in a monumental way with scaffolding.

Initially, the lights were already there as a layer in the images, similar to those at Le Petit Port.

Brent: The digital photographs ‘And then there was Light’ was part of the ongoing ‘Transitions’ project, and also related to the billboards?

Guido: Yes, in essence a part of that same series, but a bit later executed.

Brent: Can we talk about two assemblages, one in Leiden with taped elements holding the whole thing together by Swiss  artist, Daniel Gottin: And the other at SNO, Marrickville, again with a structure holding the architecture and things in it in taught/but playful space, this time a circular motif created by John Adair?

artist, Daniel Gottin: And the other at SNO, Marrickville, again with a structure holding the architecture and things in it in taught/but playful space, this time a circular motif created by John Adair?

Guido: These are the Assemblage series initiated and curated by Billy Gruner. I was lucky he put me in twice. The one at Petit Port was great fun. I remember installing it together with Jan Maarten Voskuil and Billy, mainly making a lot of noise, ha-ha. And in an instant when done all works fitted together perfectly, one after the other and together, playful and consistent. The whole combination read as one genre piece. A gesamtkunstwerk. Billy seemed to be interested in that. I consider it the best show that year in Leiden, however people may have a different opinion.

Brent: Yeah, I thought both ‘Assemblages’ worked… Billy has this idea of community, and is a bit of a raconteur, no?

Guido: Billy is a very special person in many ways and for sure he likes to speak about art. We were lucky he came along when we were busy setting up IS-projects.

Brent: I was going to leave this to the end but as it sort of has come up now, I want to ask about your IS projects, how it visually and conceptually sticks together, what influence you think it has on the community, what we call the artworld, and if it has any impact on your own work. Do you need to separate your curation/venture projects from personal art making, or are we talking all under the big top?

if it has any impact on your own work. Do you need to separate your curation/venture projects from personal art making, or are we talking all under the big top?

Guido: Yes, IS-projects… You know we already had this idea in 1999?

We actually executed an exhibition in our house in 1999 with our own work. After that, we thought group shows would be much stronger. This idea stuck in our heads and when we were able to renovate our house we made sure to make it for art and life, for IS. Lucky us, my sister is a very good architect and she helped so much. Prior to this we had asked Matthew and Rosanna from Minus Space to open things up, wanting to work with them to include Dutch artists. And then came Billy… October 2007. Three days later we had over twenty artists to choose from. Le Petit Port had a gap in the program, so we could extend: lucky, again. Then, Iemke–being educated as a print maker–initiated the idea of the edition. And since I have the digital printing background I could support and cover that direction too. Seven weeks later or so, IS opened with UND Jetzt with the presentation of that IS box set. Everything followed from that. We started a blog on the run… stuff like that.

So, IS-projects organizes two group shows a year connecting Dutch artists with artists living abroad. We choose from our personal point of view. Most of the artists actually come and we offer the artists a new audience and vice-versa. And somehow the word is spreading. People respond to it. We find it amazing how things develop. What we do like is that our audience are not only the artists, maybe 30% to 50% max. The editions seem to be a special IS feature but there is no rule, really.

So, IS-projects organizes two group shows a year connecting Dutch artists with artists living abroad. We choose from our personal point of view. Most of the artists actually come and we offer the artists a new audience and vice-versa. And somehow the word is spreading. People respond to it. We find it amazing how things develop. What we do like is that our audience are not only the artists, maybe 30% to 50% max. The editions seem to be a special IS feature but there is no rule, really.

For the IS @ SNO presentation we have made this special 25 -25 IS box (25 artists multiples 25x25cm.) It was a smart way to make a compact exhibition. We sold quite a few but it is still available. (Only 395 EUR). Spread the word. ;-P

Agent provocateur. Now I know… you know more about me than I about myself!

IS-projects is just something I do, like making art. That is the ‘big top’ part. It is connected to us. At the same time, I am not eager to put myself in our own shows: preferably not. Also, Iemke, IS-projects, and I are not a package deal. There is definitely a separation. SNO was different though, we were asked as ‘Guido and Iemke’ being artists and the directors of IS-projects. But like I said… there is no rule.

Congratulations Guido and Brent, very nice piece!