Brent: At first glance what appears formal, color oriented, geared towards the minimal, turns out to be more than the sum of the economy of a painting’s means. What serendipitously moves towards the ‘anything goes’ is in fact facilitated by a number of very considered alterations and decisions. While the surface does not necessarily show what lies beneath the final stage in the painting it is very much indebted to what has gone on before.

Simply enough, at the beginning of a painting everything seems possible. When you get to where you are happy, when the painting arrives, in a sense you are back with the viewer, where you started: with a presentation of a few lines, color, and an arrangement. And this is how it goes.

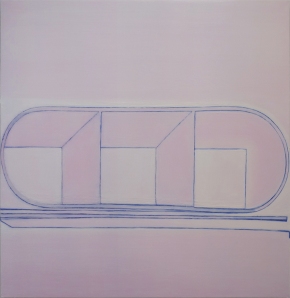

Paul: In my last couple of shows there have been individual paintings dealing with line, surface, color, edge, image,  narrative, abstraction, painting as object, pushing the limits of my vocabulary.

narrative, abstraction, painting as object, pushing the limits of my vocabulary.

Most of my work goes through an extreme form of self-introspection and mise en question to bring them to some level where the possible is arrived at. Each painting has its own set of problems from where the painting takes its roots. In your question regarding possibilities: I feel to allow the possible to enter as a starting point is very important as it defines the issues in a painting that I’m setting out to deal with. A painting arrives at this some level of the possible when I have gone through questioning, altering, changing, allowing, resuscitating from near failure and going further than what I started out to do; the painting then pulsates with a particular form of magic wherein a new limit arrives.

As far as the ‘anything goes’ it depends on what you mean. When you look at the work I have been making for the last 10 years it seems more like a search, an opening up, to find the limits of the painting language in the form it is meant to take, and not an acceptance of ‘anything goes’. Every move within the painting, or from one painting to the next has a multitude of decisions in the making.

I used to dive into a painting and battle through, bringing the painting to completion in that way. The color would change drastically – a painting starting in red could finish green, blue or yellow.

While today the same color change may happen I don’t go about it in the same way. Now I start with a more concrete idea of form or line structure, deciding on the color slowly, often after building the painting in white and gray first. The alterations are now less extreme and only happen when I am totally convinced the changes are the way to go. That said it is rare that a painting ends the way I intended it to be.

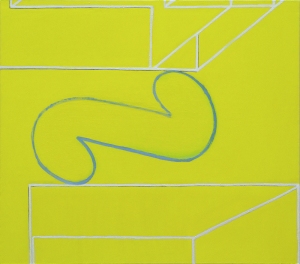

With ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ some parts of the initial pictorial idea held. However not in its figure-ground relationship, or as form as free-floating volume. The curved central yellow element stayed, and is what I set out to use. Tackling a ‘ridiculous idea’ to see if it could work, in a sense, does bring up the idea of ‘anything goes’, and could be applied here.

With ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ some parts of the initial pictorial idea held. However not in its figure-ground relationship, or as form as free-floating volume. The curved central yellow element stayed, and is what I set out to use. Tackling a ‘ridiculous idea’ to see if it could work, in a sense, does bring up the idea of ‘anything goes’, and could be applied here.

Brent: A ‘work-in-process’ has no guarantees, as what is tenable can rarely be reduced to the logical. I would even go so far as to suggest that with your painting the formal appears bound by the illogical, that the liveliest condition arrives at the precipice of the sensible.

You have suggested that painting is about a number of things: abstraction has a narrative; there is figuration, or a figurative bent. In your case a surrealistic abstraction has somehow coiled around the formal elements and pulled tight the geometric persuasion, which springs forth into a readily available motif. I would support that you are saying it isn’t about one thing, or a singular gestalt. And the gestalt involves a sensorial overload, as well as a deprivation, where at the final stage/image a painting becomes ready for us.

Paul: I like your definition of the formal being bound by the illogical, for if something is too logical what else is there to know? I personally prefer to not totally know how a painting will become; with this approach there lies the possibility of discovery and freedom.

The physical working process, as much as it is necessary and very much integral to my work, is not the whole picture. Instead it is a way through to get to the result.

Process for process sake and process painting is too limiting. For me, what remains paramount are the direct issues within painting, and how they fit into a development of this dialogue with the subject, the subject of painting.

My mother was a painter and I’d watch her paint as a child. She’d paint us children, place a mirror behind her while she painted, and that way I could see what she was doing. She would take me to museums a cross Europe; it was like a gift, giving me a trove of vivid pictorial memories.

cross Europe; it was like a gift, giving me a trove of vivid pictorial memories.

As a child I had a bad stutter so the only thing that really mattered was painting and going to museums. Painting became a second language, or even the first, for that matter.

After leaving England at the age of 9 for Austria, then to France, I realized that painting was the only language that didn’t need to be translated, that it was something I could understand no matter which country I was in.

I want the viewer to be able to look at one of my paintings and to be drawn in, as if placed in suspended time, to be totally immersed with its subject – painting, in flux with the color and structure constantly in transition.

It is funny that you bring up Surrealism as I have been thinking of it recently but wouldn’t view my work as being ‘surrealist’, even if I have been using aspects of it. That said I am drawn to its quirkiness. There’s a sense of play that I like, and I enjoy Surrealism’s ability to put work on edge, setting it off beat. Unfortunately Surrealism gets lost in its own subject matter and loses the issues of painting, turning them into what become pictorial puns. Fundamentally what I want to do is make paintings that bring you back to painting. And I find that Surrealism uses painting to express subject matter other than that of painting. The painting I am doing is not about a number of things but more precisely many related elements.

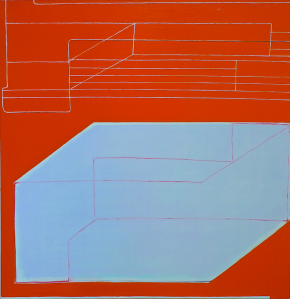

Brent: ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge‘ is a large painting that registers intimate. You mentioned starting with gray to then build with color. And I can see this in the progress images that you provide. The first image reads line: a drawing of a box almost fills the lower part of the painting. This pulls right and is painted in pinkish-red. The line work doesn’t actually complete a box. However the new blue lines pull the box into focus while suggesting also a new shape, which then brings into relation the whole canvases’ edge. The line and the smudging at the top of the painting tells that early on you had decided to build a tilting form but needed tim e to figure how to address the incongruent spaces that you had created so far.

e to figure how to address the incongruent spaces that you had created so far.

A new stage takes out most of the blue line. A lighter blue, or white, gets added, red gets added; the box loses form but still manages to locate.

Red fills the top area. Pink gets added which works to take out some of the passivity between what is going on above with the form and with the structure that sits beneath. This I see as the bringing together of a formal and pictorial logic: but you are not done.

At this stage it is clear that you work to make something almost sensible, but then pull back. I see it everywhere within the stages… making decisions, making sure that you leave an opening as an entry to go back to work or shift.

There are further changes this time; the softening of the harsh red to a more palpable orange; reintroducing the tilts, multiplying them; restating a more robust form that had started to creep in at the top. Oddly, now, the empty box area below is not quite there. The blue work is gone. Light blue and orange is now the defining edge for the painting. You have brought the opposites together without losing either one: that is hard-won. The painting is not far from where it began but is now resolved, simplified, and clear. The two aspects of the painting work together as a painting; the attention to the edges of the canvas within the content on the surface reads more than adequately austere, and it is a win.

Paul: Before I get to ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge’ what I should mention is that I can have up to eight paintings going at the same time. While I’m working intensively on one there can be two or more other visible paintings waiting with other works at various stages with their face turned round.

I will bring a painting that I’m focusing on to a limit, not to a finished limit but a worked limit, at which time I will set the painting aside and go to the next painting.

I can leave a painting in different unfinished states turned around from view for months.

With ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge’ I set out to paint a painting in a light blue field that halfway into the process of its fabrication became red. The red acted as cutout, which defined the shape of the lower form.

With this painting I had a definite idea for the structure. This may have been the problem, and why, in the end, it took so long to resolve. But I needed to tackle the seemingly irreconcilable where a lower form was meant to contradict its own direction and to flatten out. Because of this illogical structure I created a mirrored upper form, connecting both the lower and upper forms to the left edge to have the painting’s energy read from left to right. But the more I worked on the painting the more it seemed to completely refuse to play out the way I wanted it to. As of April 09 more than 7 months into the painting the lower boxlike shape was defined and was echoed by a similar form above, although not a box shape. At this point the painting, which was predominantly light cool blue, strangely read as figurative and needed a radical shift, an element that would flip the painting, challenge the illusionistic space, negate the depth and the unwarranted representation. Here I came to the decision that I needed to introduce an opaque color that would act as form. One morning after my son had gone off to school, red literally broke into the canvas unsettling the safe space the painting had settled into, the desire to put down this red had been haunting me for quite a few days, I had to summon up enough courage to go ahead with it.; due to the fact that it was going to fundamentally change the painting and that I had to be completely sure. The red enabled the painting to address the ground radically activating and altering the paintings’ dynamics.

The painting thus went from being a painting of line describing form on a field of light blue to a painting that was predominantly red; the red added a new element and acted as drawing to generate another shape and that at the same time would be its own volume. Although it didn’t completely resolve the painting’s issues, it had opened up doors to a pictorial complexity that interested me.

A few months later I arrived at a nearly possible resolution for the painting with the two forms, which sat within the red as if there was a conversation going on, the upper form remaining a little daunting; I had painted on the right side of it a flat green shape and painted gray-white lines into the red to off set the red as form, which also echoed the lower shape (these gray-white lines played an important part in resolving the painting nearly a year later). By this point in the painting I had reached the limits of the possible.

I turned ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge’ around and started to finish ‘Inner Dasein’ as well as ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ a painting that was also causing me trouble. I set about working on some other paintings that were going to be put in the Paris show. After sending off the work for my exhibition at la Galerie Eric Dupont more than eight  months had past, I decided to take up the painting again and resolve the issues that were bothering me. I scrapped the upper form, painting over it by extending the red. Though through the process of reworking the painting an upper element did come back but instead of color shapes reacting beside color it came as a white-gray linear structure with a black line acting as drawing and shadow running along one of the gray-white lines. This linear structure defined space in a field of color, it felt as if I had at last freed the painting, the ‘idea and concept’ gave way, replaced by that of painting, I had let go of the initial plans, while holding onto some of the structural elements, allowing (not without difficulty) the painting to evolve into what I hadn’t expected.

months had past, I decided to take up the painting again and resolve the issues that were bothering me. I scrapped the upper form, painting over it by extending the red. Though through the process of reworking the painting an upper element did come back but instead of color shapes reacting beside color it came as a white-gray linear structure with a black line acting as drawing and shadow running along one of the gray-white lines. This linear structure defined space in a field of color, it felt as if I had at last freed the painting, the ‘idea and concept’ gave way, replaced by that of painting, I had let go of the initial plans, while holding onto some of the structural elements, allowing (not without difficulty) the painting to evolve into what I hadn’t expected.

A lot of my paintings and drawings go through a similar form of pictorial mis en question, my work happens in the making, there is an unknown in each piece, I may have a visual idea of what the work will be, color, a scheme, structure, but as soon as I start working these ideas evolve, the painting starts its journey, for me a painting comes as a journey. New elements arrive through the multiple alterations as the painting goes on, but this said I think the first gesture that is put down will have repercussions throughout the painting, like here with ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge’.

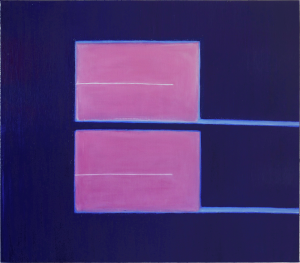

Brent: Through the adding and alteration of the marks, lines, color and overall structure of the painting the surface starts to build its own story. I wouldn’t necessarily call this a dialog with gesture as it feels you paint quite plainly: you place color or line, and after a while the surface becomes quite tactile. With ‘Inner  Dasein’, which is predominantly blue, the surface holds the multitudinous; marks made from battles that in the end hardly show themselves, except for what is left under the top skin. How important is this to the completed painting?

Dasein’, which is predominantly blue, the surface holds the multitudinous; marks made from battles that in the end hardly show themselves, except for what is left under the top skin. How important is this to the completed painting?

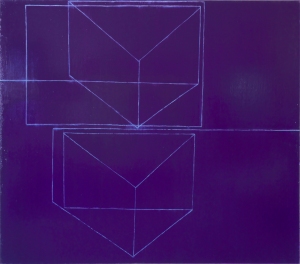

Paul: The painting has a different hue than what the photograph suggests. It’s closer to purple.

With ‘Inner Dasein’ there were no actual battles, per se, as there were with ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ and ‘Aligned Deep Down from Above on the Edge’ as I mostly stayed close to the initial concept and structure. What happened here is more rooted in the fabrication and process which would allow the painting to arrive at the pictorial, was a matter of pushing what was already in place, adding or taking out specific lines, to put them back in, in a slightly different place.

It had to do with finding the perfect angle, where a line crossed over and under another line; a matter of getting the right color for the ground or surface space which from the onset was an alteration of going back and forth between blue and purple; and the color of the lines that were first painted in yellow.

The lines became an ice blue neon color. The linear forms appeared as if they were set in space and made of light, but the actual elements were not renditions. I worked on the dimensions of each linear form, I focused on how they would read between each other and within the painting as a whole, how they should indicate volume as well as reading flat; how the neon-like cobalt lines would relate to the entire size of the painting and react within the color of the purple field.

The structure of the cobalt lines had to have a seemingly logical function as if they were composed of a single line and that the more one looked at them the more complex and intimate they would become. One of the main issues was finding the exact ground color and transparency. At one point I nearly lost the painting due to a strange desire to make the purple ground less to do with color (it had morphed into a muddy gray but I suppose a necessary passage to go through to come back to what is the final purple color that I was striving for).

For this painting I painted the linear structure into the wet purple ground and then painted over that to cover the whole painting so in one breath there was the ground color, creating this feeling of depth, and the linear forms that had disappeared underneath. I would go back and forward repeating this, covering, redrawing, covering, redrawing, searching for the color, the structures, the way the ice neon blue lines were laid into the wet surface, how the purple would mingle with the freshly painted ice-neon blue, finding the right line, the right color, depth of field, and the right tension until the painting was finished.

Working on a painting, the process and literal fabrication does change the way a painting looks, does add materiality and a sense of layered time, but for the spectator to know how I got there does not necessarily need to be revealed: not knowing doesn’t hinder the possibility for there to be a dialogue between the painting and the viewer.

In the imperfect vs. the perfect, the human ineptitudes and off-beat objects that are made by hand interests me more than objects fabricated industrially. I feel objects made in this way hold the body and call that of the viewer, (I’m not saying that the works of Donald Judd or Sol Lewitt and Dan Flavin, who I admire greatly, do not also have that aptitude).

In the imperfect vs. the perfect, the human ineptitudes and off-beat objects that are made by hand interests me more than objects fabricated industrially. I feel objects made in this way hold the body and call that of the viewer, (I’m not saying that the works of Donald Judd or Sol Lewitt and Dan Flavin, who I admire greatly, do not also have that aptitude).

What I am striving for is to manifest the ‘aura’ that Walter Benjamin much criticized. It seems to me in today’s contemporary environment where one is continually bombarded with supposedly desirable images, the sanitized mass-produced perfection among which the imperfect and individually made objects will find an essential place.

Brent: Mondrian among others talks about the body, and the point you make about the object holding the body is important… I have this idea that different points of one’s body actually help to inform the decisions you make in a painting, and if they are good decisions they actually energize the body… a painting is not just this thing that we look at.

Paul: One of the issues I love about painting is that it addresses the body as well as the mind. A painting is more or less flat: so it’s tied to a world that addresses the cerebral field; we usually cannot walk around paintings, we move only in front and from both sides.

We move, the painting stays still.

The desire of the painter is to stop the viewer, to captivate and maintain the viewer’s gaze with the painting developing a problematic of time and space, space due to the position of the body in relation to the painting and the pictorial space in the painting. Painting addresses time and the body differently from some of the other arts, such as film, music, video and writing, as it doesn’t use linear time; there is no beginning, middle and end.

Painting for me has a very complex relationship with time. It has layered time, due to its frontality, to the application of paint, the process and thought through which it is fabricated; also there is no given time in looking… it is solely up to the viewer who can choose to depart from the painting with quite a good idea of what it looks like, just after a few minutes view, contrary to film and other linear time arts.

Like listening to the same track of music many times, one doesn’t have any difficulty coming back to see a painting over and over again.

This is a great conversation. The paintings are fascinating and the talk also. Thank you both.

Fascinating description of the work and process. I like Paul’s description of surrealism and the differentiations made between linear and layered time, it’s relationship to the body and it’s ability to stop time. Great to get in your head.

Pingback: Have you met…Paul Pagk? | Painter's Progress